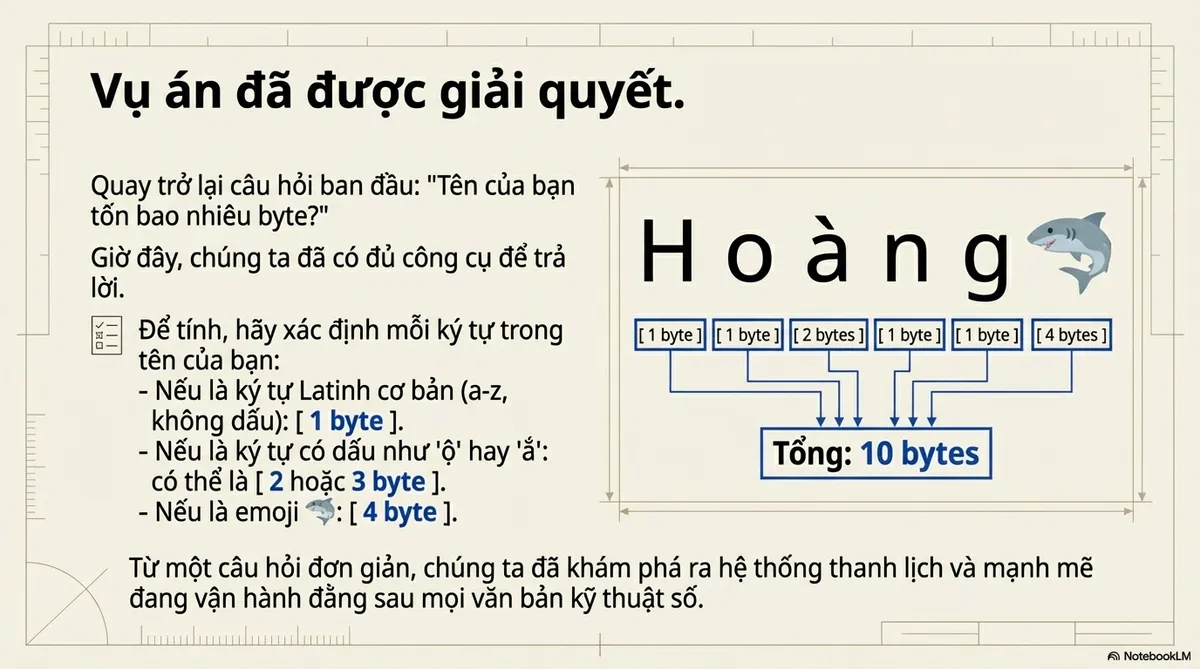

I once spoke with a colleague who could recite “1 byte = 8 bits” in his sleep, yet froze when asked, “How many bytes is your name?”

Let’s fix that.

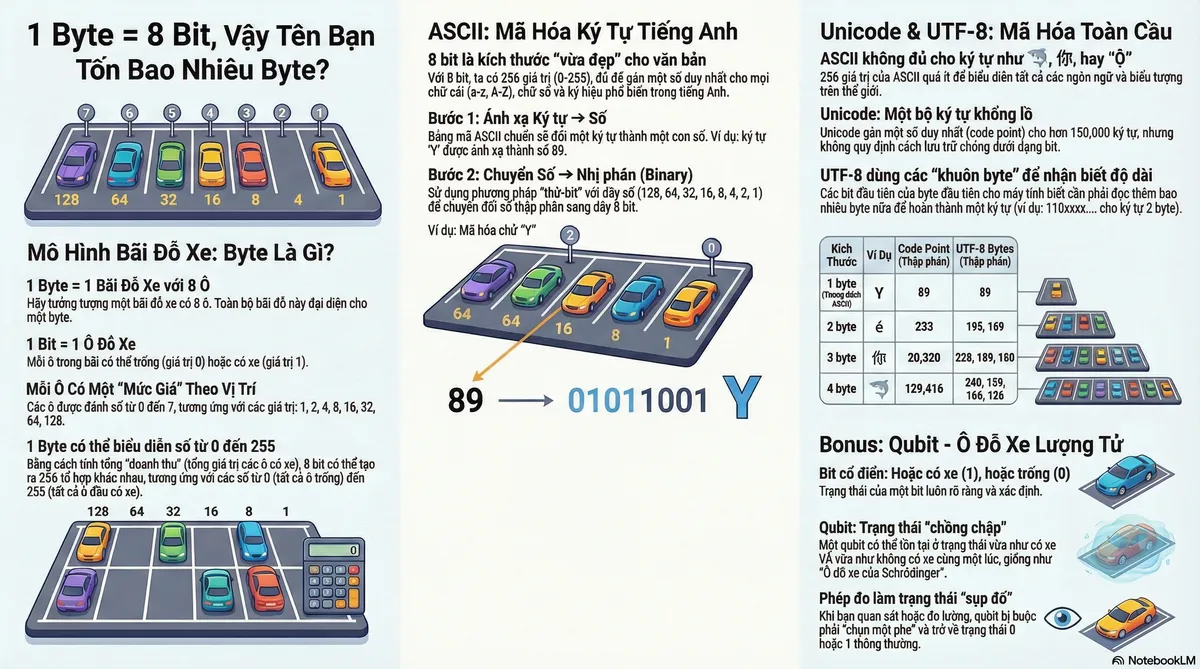

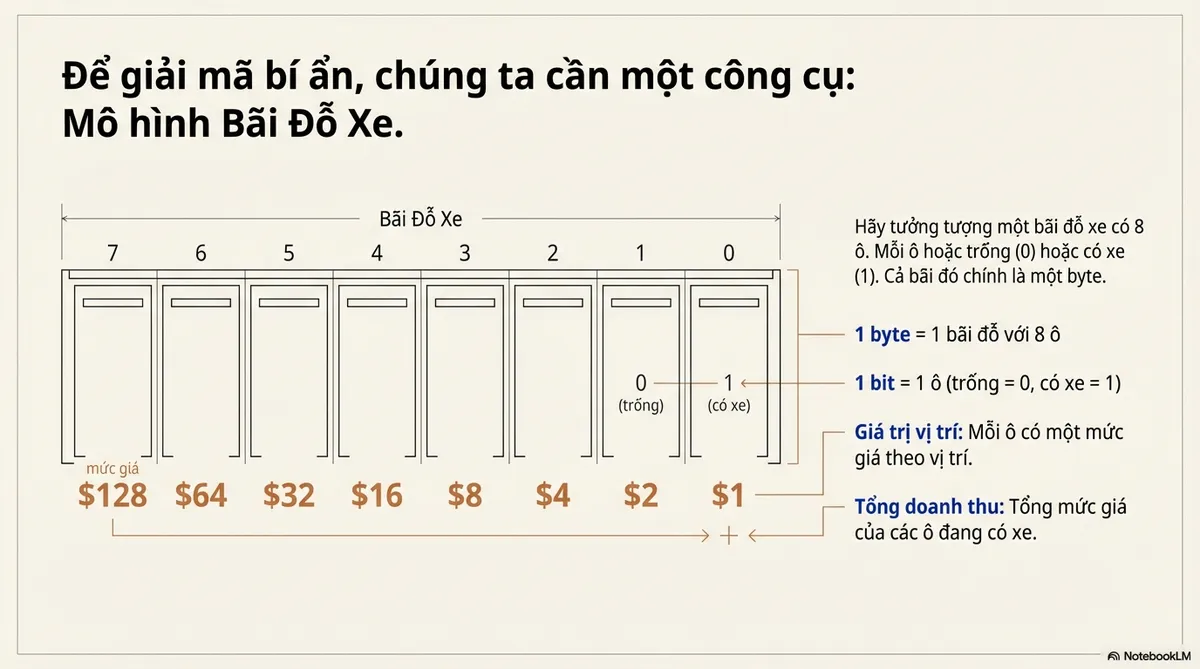

The Parking Lot Model

Picture a parking lot with 8 slots. Each slot is either empty (0) or has a car (1). That whole lot is a byte.

| Slot # | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | $128 | $64 | $32 | $16 | $8 | $4 | $2 | $1 |

- 1 byte = 1 parking lot with 8 slots

- 1 bit = 1 slot (empty = 0, car parked = 1)

- Each slot has a price tag based on position: slot 0 costs $1, slot 1 costs $2, slot 7 costs $128

- Total revenue = sum of occupied slot prices

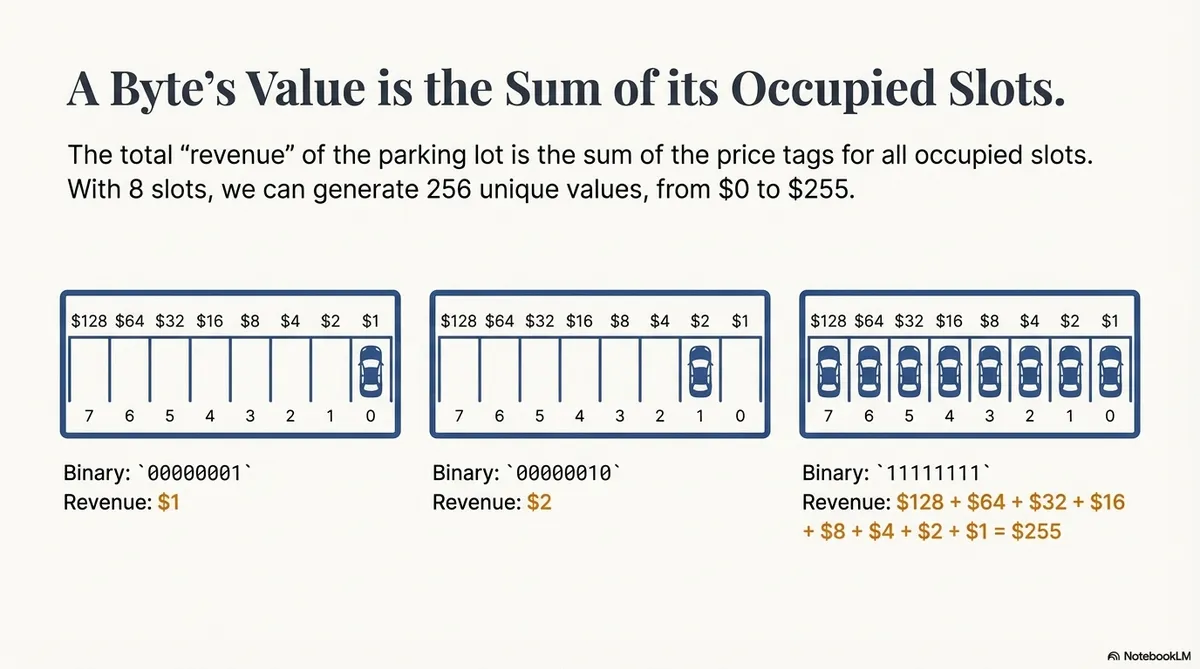

This is a visualization of how a byte is structured:

00000001 → only the last slot has a car → revenue = 1

00000010 → one car parked in the next slot → revenue = 2

11111111 → all 8 slots are full → revenue = 128 + 64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 255

The number (0–255) just depends on which slots have cars.

ASCII

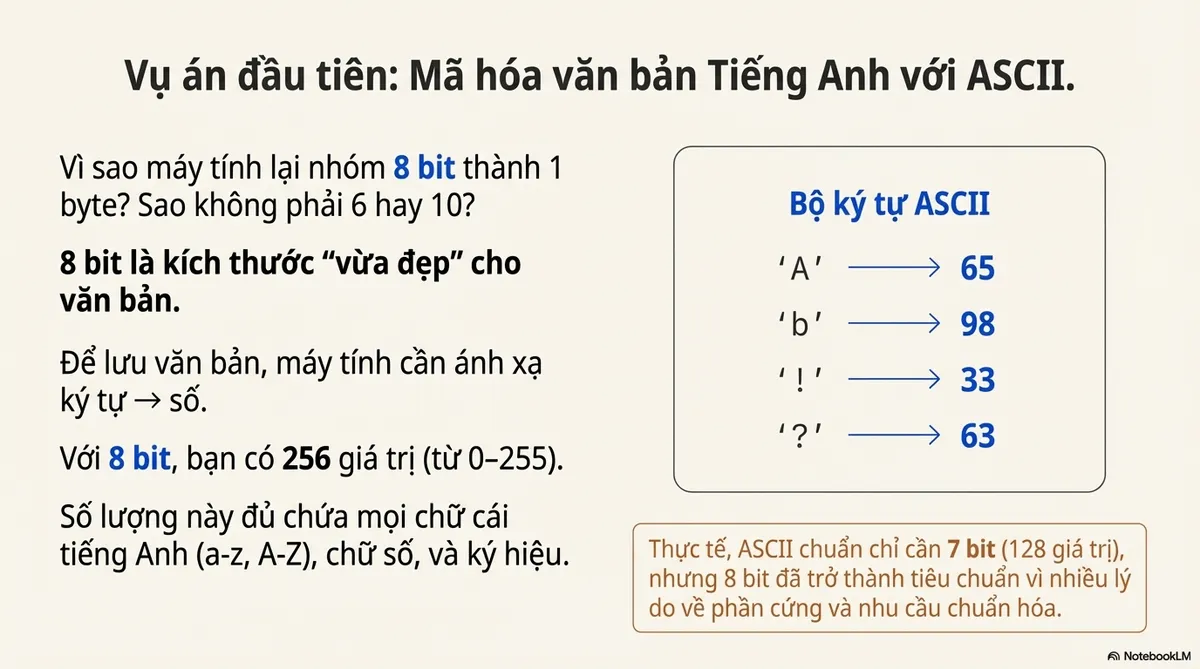

Why do computers group 8 bits (2³) into 1 byte? Why not 6 or 10?

Short answer: It’s the perfect size for text. 🐧

ASCII Character Set

To store text, computers need to map characters to numbers. With 8 bits, you get 256 slots (0–255). That’s enough space for every English letter (a-z, A-Z), number, and symbol, with room to spare.

Think of it as 256 unique parking configurations. Each one maps to a specific character.

But here’s the twist: Standard ASCII actually only needs 7 bits (128 slots).

So, why 8? Honestly, it was a mix of lucky hardware decisions and the need for a standardized “chunk” size that could handle more than just simple text.

This is a visualization of how characters are distributed across bytes:

ASCII Encoding

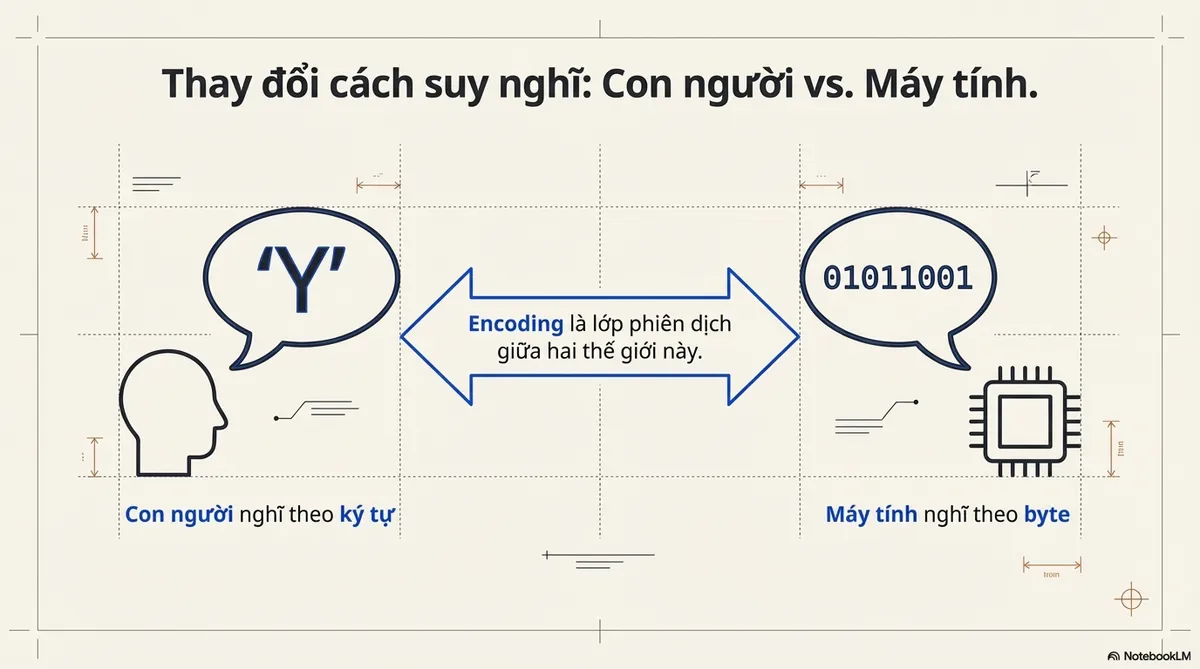

So, how do we convert between characters and bytes like the visualization above?

Let’s encode “Y” (from YELL) as an example.

Step 1: Character set Character → Number

Look it up in the ASCII table: Y = 89

Step 2: Encoding Number → Binary

Here’s where most people get stuck. Use the Bit-test method. Memorize this sequence: 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

Start with 89 and work left to right:

- 89 ≥ 128? ❌ → 0

- 89 ≥ 64? ✅ → 1 (89 − 64 = 25)

- 25 ≥ 32? ❌ → 0

- 25 ≥ 16? ✅ → 1 (25 − 16 = 9)

- 9 ≥ 8? ✅ → 1 (9 − 8 = 1)

- 1 ≥ 4? ❌ → 0

- 1 ≥ 2? ❌ → 0

- 1 ≥ 1? ✅ → 1

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Result: 01011001. That’s one byte.

There’s also the “Divide by 2” method for converting decimal to binary, but I find it tedious and rarely use it.

The mental shift:

- Humans think in characters

- Computers think in bytes

- Encodings are the translation layer between the two

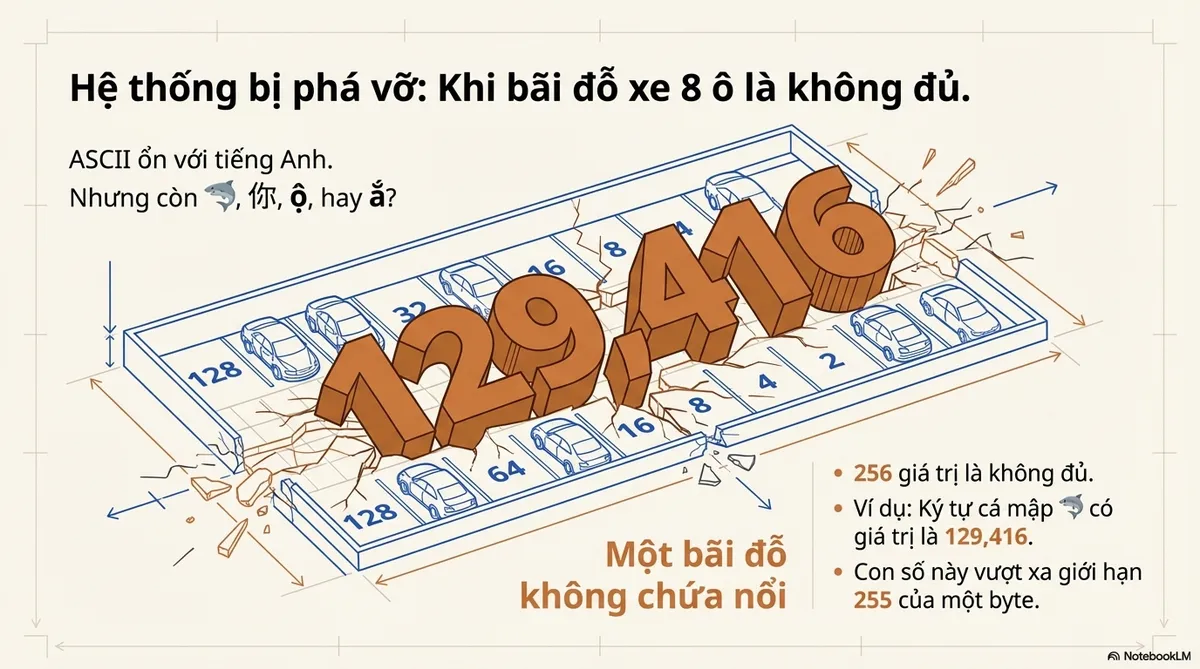

Bigger Than ASCII

ASCII works for English. But what about 🦈, 你, ộ, or ắ?

256 values won’t cut it. We need something bigger.

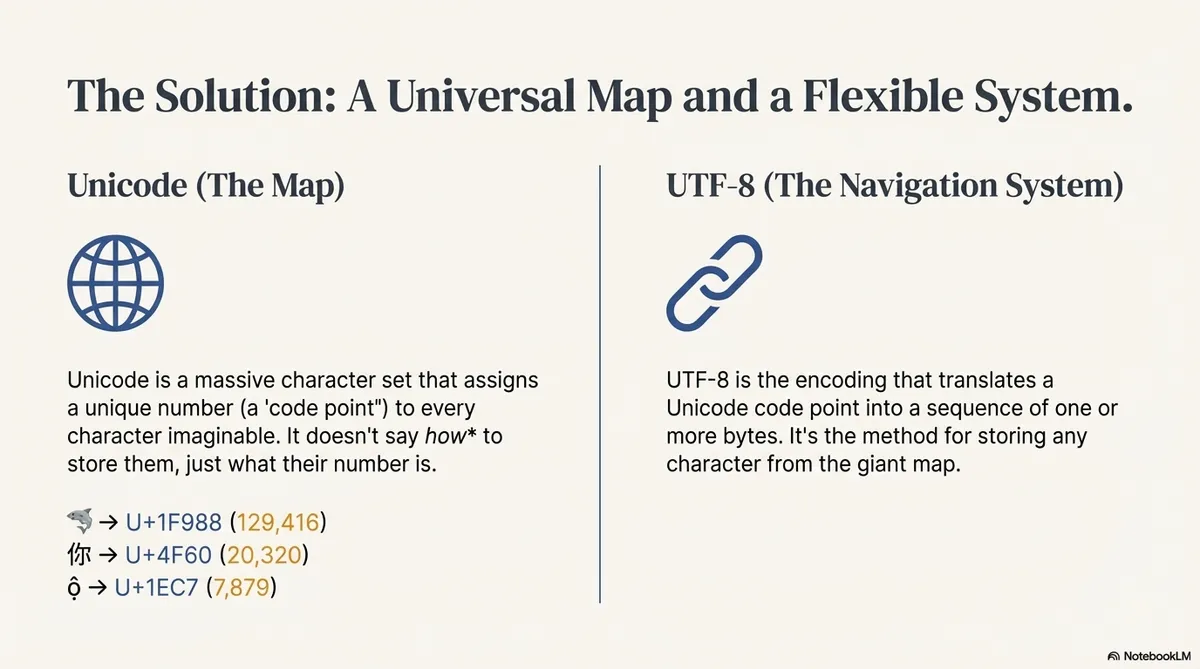

Unicode Character Set

Q: Is Unicode the same type of thing as ASCII but bigger?

A: Sort of, but not exactly.

ASCII has 2 parts:

- Character set: Convert character to decimal

- Encoding: Convert decimal to binary

Unicode is just a character set. It assigns a unique number (code point) to every character, but it doesn’t dictate how those numbers are stored as bits.

| Char | Code Point | Decimal |

|---|---|---|

| 🦈 | U+1F988 | 129,416 |

| 你 | U+4F60 | 20,320 |

| ộ | U+1EC7 | 7,879 |

| ắ | U+1EA5 | 7,845 |

Unicode 17.0 has 150,000+ code points.

The encoding part? That’s where UTF-8 comes in.

UTF-8 Encoding

Code point → bytes. How?

ASCII was simple: one character = one byte.

But 🦈 is 129,416. That’s way beyond 255. One parking lot (one byte) can’t hold it.

So, how do we distribute the cars across multiple lots to represent bigger numbers?

We need more lots.

UTF-8: The Multi-Lot Chain System

Chaining lots creates a problem: where does one character end and the next begin?

UTF-8 solves this with byte templates. The first few bits tell you how many bytes to expect.

| Bytes needed | Template |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0xxxxxxx |

| 2 | 110xxxxx 10xxxxxx |

| 3 | 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx |

| 4 | 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx |

The prefixes (110, 1110, 11110) tell the computer: “Hey, I’m a multi-byte character, read X more bytes.”

Example: Encoding 🦈

- Find code point: 🦈 = U+1F988 = 129,416

- Check range: 129,416 falls in 65,536 – 1,114,111 → needs 4 bytes

- Convert to binary: represent the code point in binary (21 bits)

- Stuff into template: distribute those bits into the 4-byte template

Apply It in Python

Python keeps text (str) and raw bytes (bytes) as two different types.

- A

stris Unicode text (code points) encode("utf-8")turns that text into the exact bytes that will be stored or sent

| |

What you’re seeing:

b'...'means: this is bytes, not text- Each

\x..is one byte written in hex (f0,9f,a6,88) - Those same bytes in decimal are

240, 159, 166, 136 - It’s 4 bytes because 🦈 is outside the ASCII range, so UTF-8 uses the 4-byte template

And you can always round-trip back to text:

| |

UTF-8 BOM

A BOM (Byte Order Mark) is an optional marker at the start of a text file that can signal the encoding (and for UTF‑16/UTF‑32, the byte order).

UTF-8 does not need a BOM. But some tools still save “UTF‑8 with BOM”, which prepends 3 bytes at the start of the file:

- BOM bytes (hex):

EF BB BF - That’s Unicode code point

U+FEFFwhen decoded as text

Most of the time it’s harmless. The annoying case is when a strict parser expects the file to start with a specific character (like { for JSON), but it actually starts with BOM bytes.

Quick checks/fixes:

| |

| |

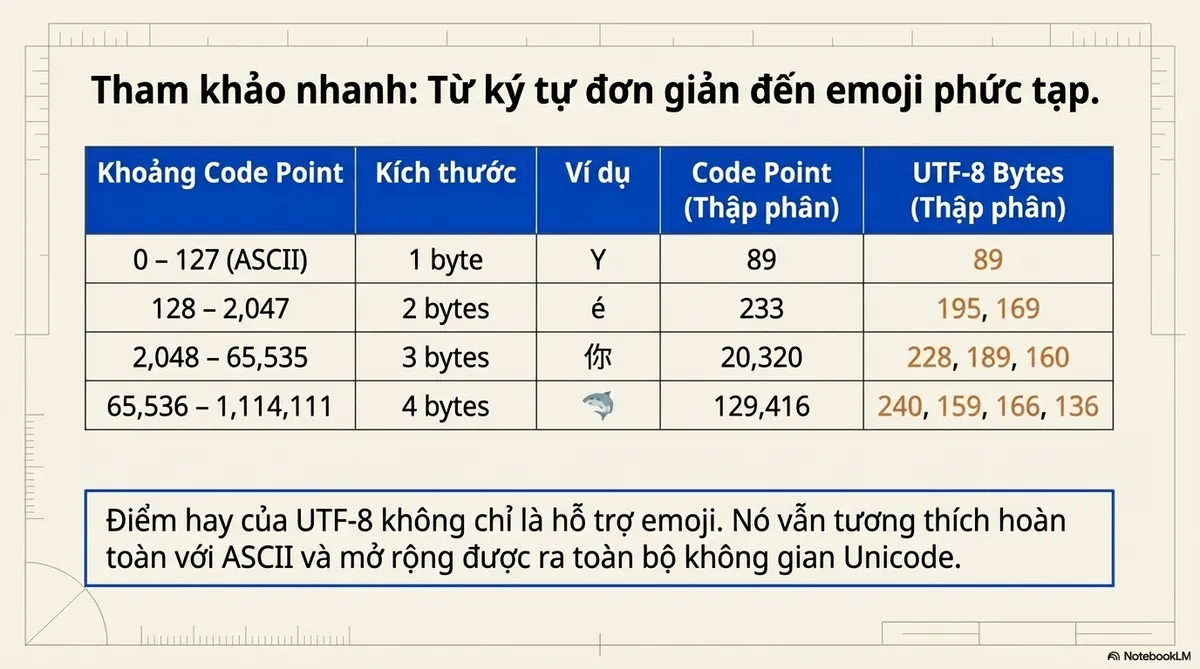

Quick Reference

| Code Point Range | Size | Example | Code Point | Decimal | UTF-8 bytes (dec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – 127 (ASCII) | 1 byte | Y | U+0059 | 89 | 89 |

| 128 – 2,047 | 2 bytes | é | U+00E9 | 233 | 195, 169 |

| 2,048 – 65,535 | 3 bytes | 你 | U+4F60 | 20,320 | 228, 189, 160 |

| 65,536 – 1,114,111 | 4 bytes | 🦈 | U+1F988 | 129,416 | 240, 159, 166, 136 |

The takeaway: UTF-8’s genius isn’t just that it supports emojis. It stays compatible with ASCII and scales to the entire Unicode space.

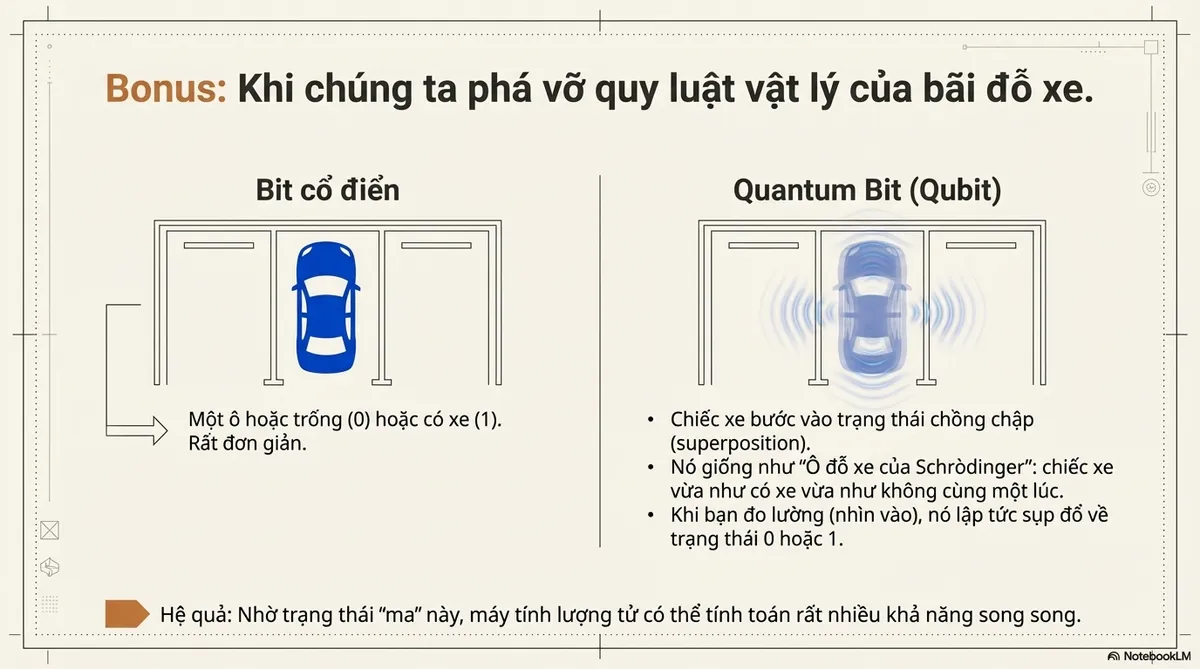

Quantum Computing (Bonus)

Let’s break the physics of our parking lot.

A classical bit is simple: The slot is either empty (0) or occupied (1).

A quantum bit (qubit) is weird. The car enters superposition.

- Superposition: The car is in a ghostly state: both parked and empty at the same time.

- Measurement: When you check the slot, the car is forced to “pick a side.” It instantly collapses into a normal 0 or 1.

It’s like Schrödinger’s Parking Spot. Spooky? Yes. But it allows quantum computers to calculate millions of possibilities at once.

Of course, with that “sometimes happy, sometimes sad” behavior, it’s used for other things. It’s not for storage the way we do it classically.